🔎 Can leverage increase risk appetite?

❔Does leverage (having a lot of debt) make risky investments more attractive?

✔ Yes, it can, particularly if the firm is already having distress.

Bruce covered this in the Equity-Debt Holder Conflict section of his presentation. Here is the key text (the original slides are below)

- Equity-Debt Holder Conflicts

- A conflict of interest exists if investment decisions have different consequences for the value of equity and the value of debt

- most likely to occur when the risk of financial distress is high

- managers may take actions that benefit shareholders but harm creditors and lower the total value of the firm

- [Think of this as: VL↓ and D↓, but E↑]

- A conflict of interest exists if investment decisions have different consequences for the value of equity and the value of debt

- Agency costs for a company in distress that will likely default:

- Excessive risk-taking

- A risky project could save the [the value of the stock, E] even if the expected outcome is so poor that it would normally be rejected

- Excessive risk-taking

The above text is taken from the following two slides:

|  |

Much of the content on this page is taken from a pair of versions of our textbook.

Equity-Debt Holder Conflicts

When a firm has leverage, a conflict of interest exists if investment decisions have different consequences for the value of equity and the value of debt. Such a conflict is most likely to occur when the risk of financial distress is high. In some circumstances, managers may take actions that benefit shareholders but harm the firm’s creditors and lower the total value of the firm.

To illustrate, put yourself in the place of the shareholders of a company in distress that is likely to default on its debt. You could continue as normal, in which case you will very likely lose the value of your shares and control of the firm to the bondholders. Alternatively, you could:

- Roll the dice and take on a risky project that could save the firm, even though its expected outcome is so poor that you normally would not take it on.

- Conserve funds rather than invest in new, promising projects.

- Cash out by distributing as much of the firm’s capital as possible to the shareholders before the bondholders take over.

Why would you roll the dice? Even if the project fails, you are no worse off because you were headed to default anyway. If it succeeds, then you avoid default and retain ownership of the firm. This incentive leads to excessive risk-taking, a situation that occurs when a company is near distress and shareholders have an incentive to invest in risky negative-NPV projects that will destroy value for debt holders and the firm overall. Anticipating this behavior, security holders will pay less for the firm initially. This cost is likely to be highest for firms that can easily increase the risk of their investments.

Exploiting Debt Holders: The Agency Costs of Leverage

In this section, we consider another way that capital structure can affect a firm’s cash flows: It can alter managers’ incentives and change their investment decisions. If these changes have a negative NPV, they will be costly for the firm.

The type of costs we describe in this section are examples of agency costs—costs that arise when there are conflicts of interest between stakeholders. Because top managers often hold shares in the firm and are hired and retained with the approval of the board of directors, which itself is elected by shareholders, managers will generally make decisions that increase the value of the firm’s equity. When a firm has leverage, a conflict of interest exists if investment decisions have different consequences for the value of equity and the value of debt. Such a conflict is most likely to occur when the risk of financial distress is high. In some circumstances, managers may take actions that benefit shareholders but harm the firm’s creditors and lower the total value of the firm.

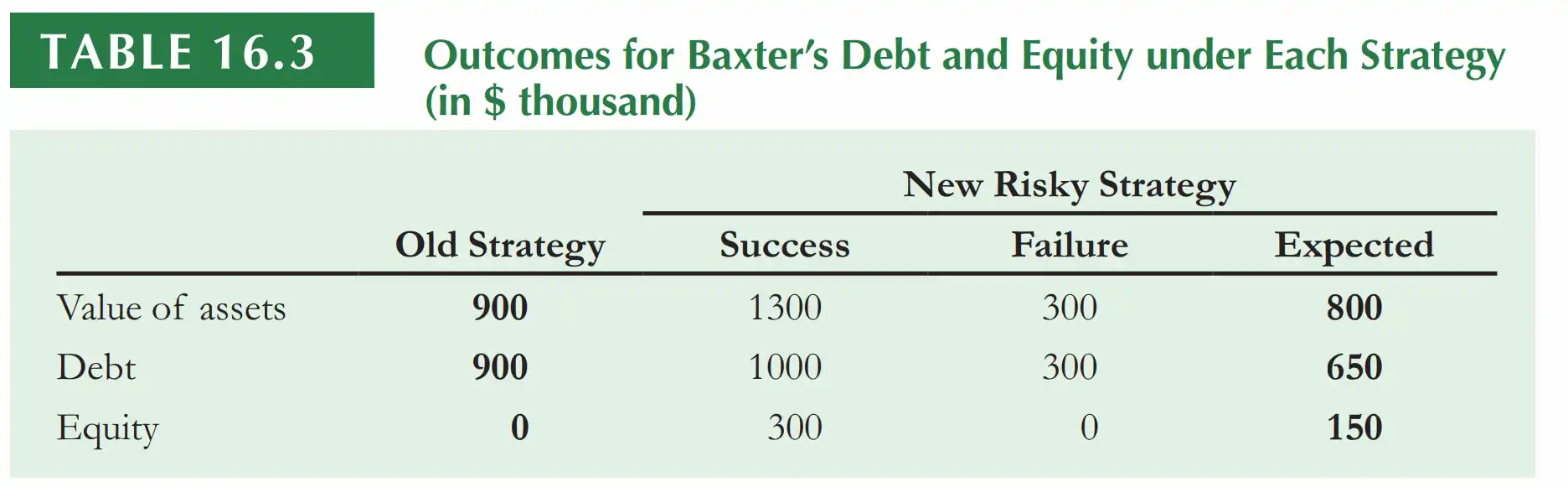

We illustrate this possibility by considering Baxter Inc., a firm that is facing financial distress. Baxter has a loan of $1 million due at the end of the year. Without a change in its strategy, the market value of its assets will be only $900,000 at that time, and Baxter will default on its debt. In this situation, let’s consider several types of agency costs that might arise.

Excessive Risk-Taking and Asset Substitution

Baxter executives are considering a new strategy that seemed promising initially but appears risky after closer analysis. The new strategy requires no upfront investment, but it has only a 50% chance of success. If it succeeds, it will increase the value of the firm’s assets to $1.3 million. If it fails, the value of the firm’s assets will fall to $300,000. Therefore, the expected value of the firm’s assets under the new strategy is 50% * $1.3 million + 50% * $300,000 = $800,000, a decline of $100,000 from their value of $900,000 under the old strategy. Despite the negative expected payoff, some within the firm have suggested that Baxter should go ahead with the new strategy, in the interest of better serving its shareholders. How can shareholders benefit from this decision?

Legend:

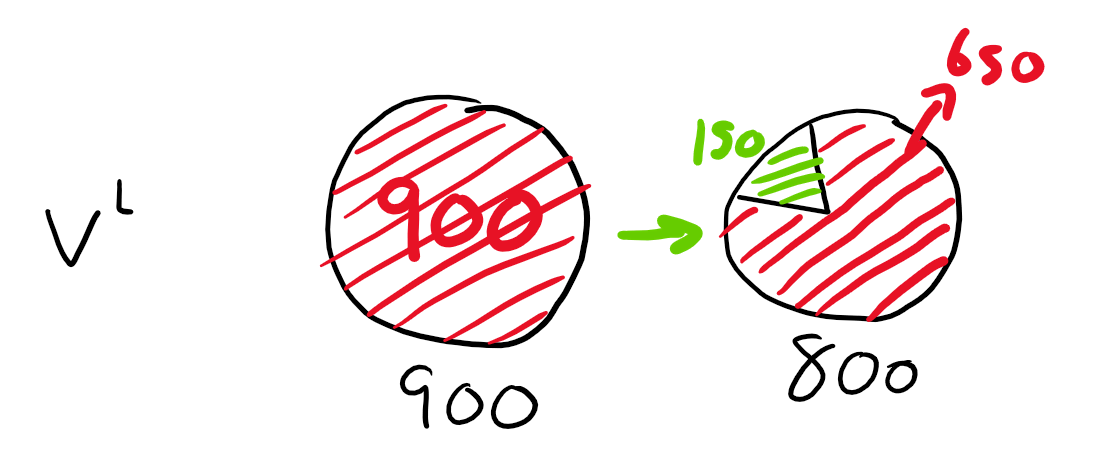

Areas in green represent the value of levered or unlevered equity (E). However, if the firm is levered, then the equity holders want the firm to take the risk. With the old strategy, the firm will only have enough to pay off most of its debt, so the equity will be worthless. However, if they take on the (bad) risky project, then there is a 50% chance that the firm will have enough money to return $300 to the stockholders. That’s much better for the equity holders, because even though it shrinks the pie, the stockholders actually get a piece of the pie.  |

As Table 16.3 shows, if Baxter does nothing, it will ultimately default and equity holders will get nothing with certainty. Thus, equity holders have nothing to lose if Baxter tries the risky strategy. If the strategy succeeds, equity holders will receive $300,000 after paying off the debt. Given a 50% chance of success, the equity holders’ expected payoff is $150,000.

Clearly, equity holders gain from this strategy, even though it has a negative expected payoff. Who loses? The debt holders: If the strategy fails, they bear the loss. As shown in Table 16.3, if the project succeeds, debt holders are fully repaid and receive $1 million. If the project fails, they receive only $300,000. Overall, the debt holders’ expected payoff is $650,000, a loss of $250,000 relative to the $900,000 they would have received under the old strategy. This loss corresponds to the $100,000 expected loss of the risky strategy and the $150,000 gain of the equity holders. Effectively, the equity holders are gambling with the debt holders’ money.

This example illustrates a general point: When a firm faces financial distress, shareholders can gain from decisions that increase the risk of the firm sufficiently, even if they have a negative NPV. Because leverage gives shareholders an incentive to replace low-risk assets with riskier ones, this result is often referred to as the asset substitution problem.20 It can also lead to over-investment, as shareholders may gain if the firm undertakes negative-NPV, but sufficiently risky, projects.

In either case, if the firm increases risk through a negative-NPV decision or investment, the total value of the firm will be reduced. Anticipating this bad behavior, security holders will pay less for the firm initially. This cost is likely to be highest for firms that can easily increase the risk of their investments

❔Does already having leverage increase appetite to take on risky projects?

✔ Yes.

Take a look at the following slide. As it mentions, “managers may take actions that benefit shareholder but hard creditors and lower the total value of the firm.”

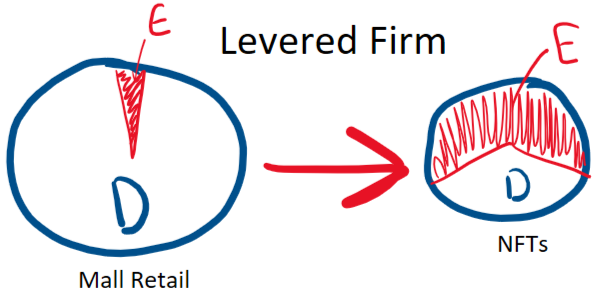

The following example is based on Gamestop’s decision to enter the very risky world of creating a NFT marketplace. This probably decreased the total value of the levered firm. In other words, VL = D + E likely decreased. However, while the market value of debt likely decreased (compared to what it would have been if they had just stuck with their core competencies), it may have actually juiced the stock price of the firm. In other word, D probably went down and E went up. In total the value of the levered firm (D+E) probably declined.

On the left, the goal of NFTs was not to increase the size of the pie. It was just to steal pie from the debtholders. Because of this, when a firm has debt, there is pie to steal, and under some circumstances, the equity may take risky projects like the NFT marketplace GameStop started, in order to steal pie from the creditors. It does this even though it shrinks the value of the entire firm (VL)

🕣

❔In the GameStop example, the reason that equity is able to grab a larger share of the pie is because, as you mentioned, creditors absorb some of the risk.

✔ In other words, the GameStop example is meant to be consistent with your understanding when you said, “equity holders are more likely to take on a risky project because creditors absorb some of the risk.”

The idea is that the firm already has so much financial distress that with the risky venture, thecreditors may not get paid. Another way of looking at this is to say that the creditors are absorbing some of the risky project. Because the project decreases the total value of the firm, then normally it wouldn’t be accepted. However, stockholders have more control, and they are only interested in the performance of equity shares. Because they don’t carry the full risk of the venture, it is still a plausible venture for them.

Moonshot:

| P | CF | |

|---|---|---|

| good | 10% | +100M |

| bad | 90% | -100M |

the EV = 10%*100 - 90%*100 = -80

| without the risky project | With project good case | With project bad case | Expected Value with project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debit | $100M | $200M | $0M | 10%*200+90%*0= $20M ↑ terrible, “excessively risky project” |

| Cash Flows to Equity | $0 | $100M | $0 | $0M 10%*100+90%*0 = $10M |

| Cash Flows to Creditors | $100M | $100M | $0M |

Market Cap without risky project = $0/8% = ($0.00) ← using the perpetuity formula

i=8%

Market Cap with the risky project = $10/30% = $33.33

i=30%

Nick Leeson

A sidebar from this section of the textbook on an important topic:

Global Financial CrisisMoral Hazard and Government Bailouts The term moral hazard refers to the idea that individuals will change their behavior if they are not fully exposed to its consequences. Discussion of moral hazard’s role in the 2008 financial crisis has centered on mortgage brokers, investment bankers, and corporate managers who earned large bonuses when their businesses did well, but did not need to repay those bonuses later when things turned sour. The agency costs described in this chapter represent another form of moral hazard, as equity holders may take excessive risk or pay excessive dividends if the negative consequences will be borne by bondholders.* How are such abuses by equity holders normally held in check? Bondholders will either charge equity holders for the risk of this abuse by increasing the cost of debt, or, more likely, equity holders will credibly commit not to take on excessive risk by, for example, agreeing to very strong bond covenants and other monitoring. Ironically, despite the potential immediate benefits of the federal bailouts in response to the 2008 financial crisis, by protecting the bondholders of many large corporations, the government may have simultaneously weakened this disciplining mechanism and thereby increased the likelihood of future crises. With this precedent in place, all lenders to corporations deemed “too big to fail” may presume they have an implicit government guarantee, thus lowering their incentives to insist on strong covenants and to monitor whether those covenants are being satisfied. Without this monitoring, the likelihood of future abuses by equity holders and managers has probably been increased, as has the government’s liability. |